AWS Lambda: Testing the Waters

Monday, January 5 2015

In a previous post I waxed poetic about the potential of AWS Lambda. Now it’s time to actually use it.

As this is a “testing the waters” post, we won’t be building anything particularly useful or production-ready. Instead, we will work towards implementing one of the very first ideas I had for a Lambda function: running GitHub Gists in the cloud. This strikes me as interesting for several reasons:

- Instant decoupled versioning. Currently Lambda’s versioning system is at best n+1 and at worst nonexistent, whereas Gists are backed by git and separated from the AWS infrastructure.

- Consolidation of one-off Lambda functions into a single “uber-function” …rather than manage dozens of Lambda functions that do silly things like MD5-hash a string or add two numbers.

- Easier sharing of public functionality. Letting other people run your Lambda functions entails the horrors of IAM roles. On the other hand, everyone can see your public Gists.

- All the other benefits of GitHub (sharing, comments, forking, etc.) for Lambda. Hooray!

Alright, let’s get to it!

Step 1: Running Arbitrary Code

NOTE: Whenever you hear something like “arbitrary code” in the context of JavaScript, it usually means

eval()(or something like it) is involved. It should go without saying that careless use ofeval()is a really bad thing. But we’ll be careful.

As we will basically be pulling in code from a URL and then evaluating it against some arguments, it makes sense to first construct a system for evaluating functions stored as strings. Once this is done, we can replace the string with the result of a GET request to GitHub’s Gist API.

Before going any further, we need to define a protocol for how these Gists will be structured and evaluated. Initially I considered simply storing the entire function in the Gist and passing args in as an array, which requires a straightforward eval() and apply(). However, this presented several problems. The first was that eval() does not return the evaluated code — or even an AST of it — but rather injects it into the current scope. This means that there would be no way to bind the function to a callable variable short of prepending var f = to the string, but doing so requires knowing how the function was defined. The second problem was that managing the args as an array independent of calling the function just felt weird. In other words, I needed some way to “match” the args to their application — i.e. a dictionary.

My solution was to store only the function body in the Gist and use an argument dictionary instead of an array. What does this mean? Well, suppose I have a function like this:

var add = function(a, b) {

return a + b;

};

Then my Gist would be:

return a + b;

And my arguments would be something like the following:

{

"a": 5,

"b": 3

}

Note that although this restricts the Gist to one function body, you can still do remarkable things in a single JavaScript function thanks to function closures.

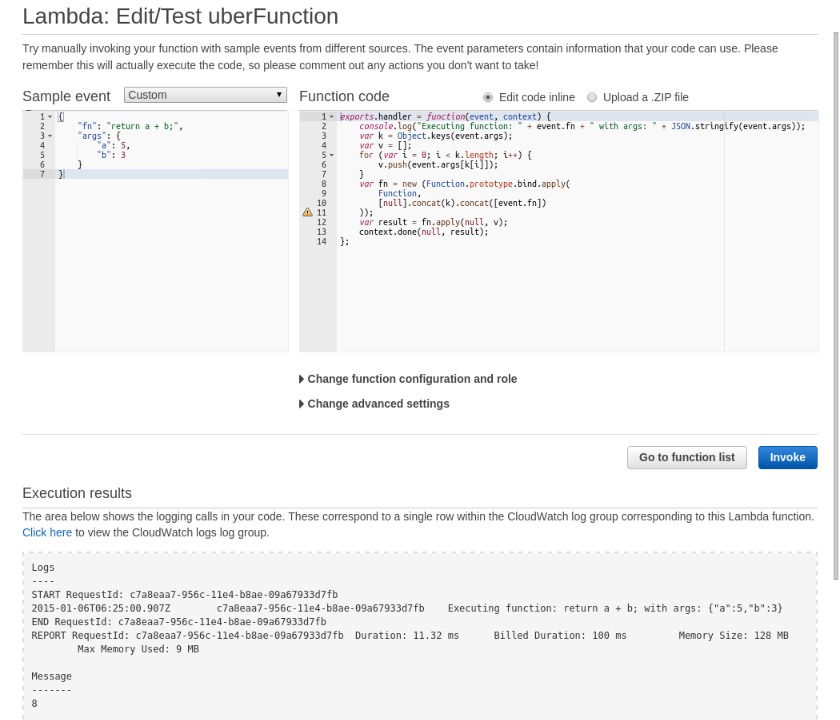

Whew! I think it’s about time to get to some coding. First, create a new Lambda function from the AWS Console (don’t worry about the code for now as you can always edit it later; just use one of the default samples) and navigate to the editing view by clicking the Edit/Test button. From here, you can modify your code and test it out by invoking it with manual events, then see the results in realtime.

At this point I know I want my function to handle an event like the following:

{

"fn": "return a + b;",

"args": {

"a": 5,

"b": 3

}

}

The first thing to do is get the argument names and values:

var k = Object.keys(event.args);

var v = [];

for (var i = 0; i < k.length; i++) {

v.push(event.args[k[i]]);

}

Now for the hard part: we need to create a new function given the event.fn string and argument names now stored in the k array. A quick Google search reveals that it’s possible to do so via the following:

var add = new Function('a', 'b', 'return a + b');

However, we have the argument names as an array that must be destructured into the Function constructor. Although ES6 Harmony will make this trivial, we’re stuck with using apply() in a rather weird way:

var fn = new (Function.prototype.bind.apply(

Function,

[null].concat(k).concat([event.fn])

));

And now that our function is defined and bound to fn, we can call it:

var result = fn.apply(null, v);

context.done(null, result);

Putting it all together now (with some additional logging):

exports.handler = function(event, context) {

console.log("Executing function: " + event.fn + " with args: " + JSON.stringify(event.args));

var k = Object.keys(event.args);

var v = [];

for (var i = 0; i < k.length; i++) {

v.push(event.args[k[i]]);

}

var fn = new (Function.prototype.bind.apply(

Function,

[null].concat(k).concat([event.fn])

));

var result = fn.apply(null, v);

context.done(null, result);

};

Run that with the aforementioned event, and you should see the following:

Through a large and completely unnecessary series of abstractions, we have gotten the cloud to add 5 and 3.

Step 2: Fetching Gists

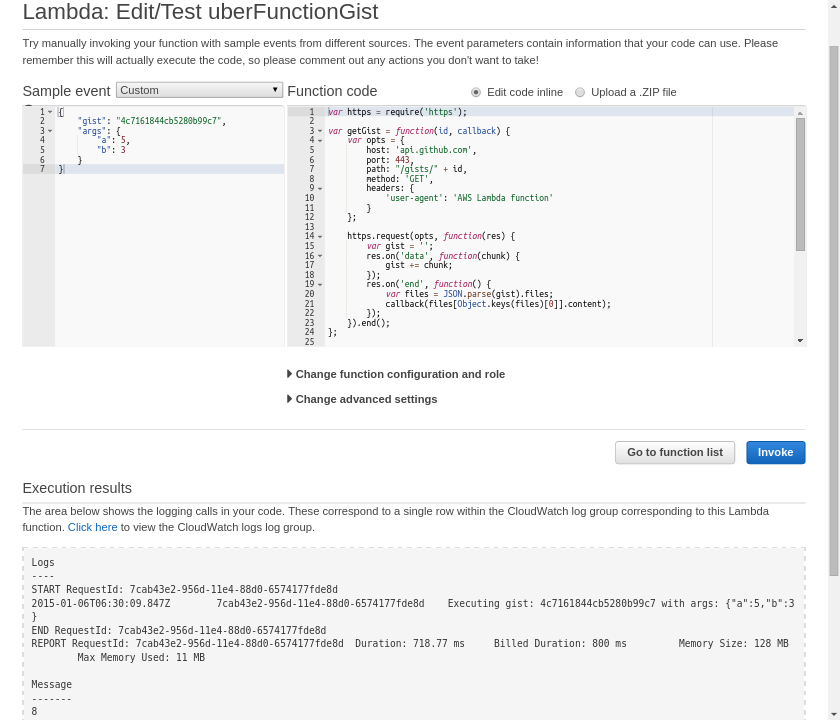

Now instead of inlining our function in the event, we’ll provide a Gist ID:

{

"gist": "4c7161844cb5280b99c7",

"args": {

"a": 5,

"b": 3

}

}

Which points to this Gist:

| 1 2 3 4 |

|

We’ll also modify our code to the following:

var https = require('https');

var getGist = function(id, callback) {

var opts = {

host: 'api.github.com',

port: 443,

path: "/gists/" + id,

method: 'GET',

headers: {

'user-agent': 'AWS Lambda function'

}

};

https.request(opts, function(res) {

var gist = '';

res.on('data', function(chunk) {

gist += chunk;

});

res.on('end', function() {

var files = JSON.parse(gist).files;

callback(files[Object.keys(files)[0]].content);

});

}).end();

};

exports.handler = function(event, context) {

console.log("Executing gist: " + event.gist + " with args: " + JSON.stringify(event.args));

var k = Object.keys(event.args);

var v = [];

for (var i = 0; i < k.length; i++) {

v.push(event.args[k[i]]);

}

getGist(event.gist, function(contents) {

var fn = new (Function.prototype.bind.apply(

Function,

[null].concat(k).concat([contents])

));

var result = fn.apply(null, v);

context.done(null, result);

});

};

The meat of the added code is in the getGist() function that, true to its name, invokes a callback passing the contents of the Gist with a given id. How this function works is outside of the scope of this post so I’ll not go over it here, but one point in particular that bears mentioning is that we restrict Gists to only a single file — note how we are only concerned with Object.keys(files)[0]. This makes sense, since logically a single JavaScript function should only be a single file.

Okay, now for the moment of truth:

Once again, AWS Lambda has produced 8 and is now batting two for two.

Step 3: The Gist Library

I don’t know about you, but I sure as heck won’t be able to remember that Gist 4c7161844cb5280b99c7 is my JavaScript add() function. So the next natural step is to create some sort of Gist “collection” mapping functions to their respective IDs, such that they can be called easily. It just so happens that this will require writing some client-side code using the AWS SDK. Along the way we’ll figure out how to get Lambda to talk back to our clients.

Oh, wait. A library with only a single Gist is kind of pointless, is it not? Let’s add another one:

| 1 2 3 4 5 |

|

In the spirit of want-driven programming, I’m going to say I want to be able to define a JavaScript object like the following as my library:

{

"add": "4c7161844cb5280b99c7",

"fib": "9213e3afa774b436edbf"

}

And do this:

var lib = gistLibrary.load(/* library object here */);

lib.add({

a: 5,

b: 3

}, function(res) {

console.log(res); // 8!

});

Step 3A: Some Resources

Right now, AWS Lambda is completely event-driven. That means that when you invoke a Lambda function via HTTP request, it doesn’t just return its results. Hopefully in the future Lambda will support a REST-like endpoint, but for now we have to resort to defining a sink. In this case, an SQS queue will do nicely.

Before that, we’ll need to create a new IAM user role for what we’re about to do (this step isn’t completely necessary but is considered a best-practice):

- Go to the IAM console

- Click on “Users” in the sidebar, then “Create New Users”

- Enter a username and hit “Create”

- Click on your newly-created user in the table and scroll down to the “Permissions” section and hit “Attach User Policy”

- Select the “AWS Lambda Full Access” template for your policy, but also add

"sqs:*"under"Action"

Was that complicated or what? Thankfully, this new role allows us to access both Lambda and SQS. Now you can go over to SQS and create a new queue — this part is pretty straightforward so I won’t go through it. Take note of the queue’s URL for later.

Lastly, don’t forget to also add "sqs:*" to your Lambda function’s IAM role policy, otherwise it won’t be able to write to the SQS queue.

Step 3B: Modified Lambda Function

Our new workflow will be to invoke the Lambda function, have it post its result to the SQS queue, and poll the queue to retrieve the result. Therefore we need to modify our function to post to SQS:

var https = require('https');

var aws = require('aws-sdk');

var sqs = new aws.SQS();

// getGist() here

var postToSQS = function(url, data, callback) {

sqs.sendMessage({

MessageBody: JSON.stringify(data),

QueueUrl: url

}, function(err) {

callback(err);

});

};

exports.handler = function(event, context) {

console.log("Executing gist: " + event.gist + " with args: " + JSON.stringify(event.args));

var k = Object.keys(event.args);

var v = [];

for (var i = 0; i < k.length; i++) {

v.push(event.args[k[i]]);

}

getGist(event.gist, function(contents) {

var fn = new (Function.prototype.bind.apply(

Function,

[null].concat(k).concat([contents])

));

var result = fn.apply(null, v);

postToSQS(event.sqsQueueUrl, {

id: event.gist,

result: result

}, function(err) {

context.done(err, "Finished with result: " + result);

});

});

};

Here I have omitted the getGist() function for brevity as it has not changed.

Step 3C: Client Code

Practically all client-side work you do with Lambda will require the AWS SDK, so install that now (assuming you have npm init-ed your project):

$ npm install aws-sdk --save

First, let us add some scaffolding:

var aws = require('aws-sdk');

var gistLibrary = {};

gistLibrary.pendingRequests = {};

gistLibrary.config = function(conf) {

// @TODO

};

gistLibrary.load = function(lib) {

// @TODO

return this;

};

module.exports = gistLibrary;

Our config() function is fairly straightforward; we’ll take in some AWS keys and other necessary variables in a dictionary and store it:

this._config = conf;

aws.config.apiVersions = {

lambda: '2014-11-11',

sqs: '2014-11-11'

};

aws.config.update({

accessKeyId: this._config.ACCESS,

secretAccessKey: this._config.SECRET,

region: this._config.REGION

});

this.sqs = new aws.SQS();

this.lambda = new aws.Lambda();

The load() function is a bit more involved:

this._library = lib;

Object.keys(lib).map(function(f) {

this[f] = function(args, callback) {

var self = this;

console.log("Calling Gist with ID: " + self._library[f]);

self.addPending(self._library[f], callback);

// Set up SQS to receive a message

// Call the Lambda function

};

}, this);

As soon as a function in our library is called, we store its callback for later invocation via the addPending() function:

gistLibrary.addPending = function(id, val) {

if (this.pendingRequests.hasOwnProperty(id)) {

if (typeof(this.pendingRequests[id]) === 'function') {

this.pendingRequests[id](val);

} else {

val(this.pendingRequests[id]);

}

delete this.pendingRequests[id];

} else {

this.pendingRequests[id] = val;

}

};

Note that val may be either a result from the SQS queue or the callback defined when a function is called. This is because execution is asynchronous; it’s possible (albeit highly unlikely) that a result could be returned before the callback can be stored. When working with Lambda/SQS, and really whenever network requests are involved, one must be extremely careful to avoid assuming any sort of sequential order to one’s code.

At last, let us set up our SQS listener:

self.sqs.receiveMessage({

QueueUrl: self._config.SQS_QUEUE_URL,

MaxNumberOfMessages: 1,

WaitTimeSeconds: 3

}, function(err, data) {

if (err) {

console.log(err);

return;

}

var message = data.Messages[0];

var res = JSON.parse(message.Body);

self.addPending(res.id, res.result);

self.sqs.deleteMessage({

QueueUrl: self._config.SQS_QUEUE_URL,

ReceiptHandle: message.ReceiptHandle

}, function(err, data) {

err && console.log(err);

});

});

And call the Lambda function:

self.lambda.invokeAsync({

FunctionName: self._config.LAMBDA_FUNCTION,

InvokeArgs: JSON.stringify({

gist: self._library[f],

args: args,

sqsQueueUrl: self._config.SQS_QUEUE_URL

})

}, function(err, data) {

err && console.log(err);

});

At best, this is an exercise in correctly formatting the JavaScript objects that get passed around. Try to see how the data flows in a complete round-trip from invocation to the AWS Console — perhaps by perusing your CloudWatch logs — back to our pending queue.

Step 3D: Using the Library

This is best illustrated with a code sample:

var gistLibrary = require('./gistLibrary');

gistLibrary.config({

ACCESS: '[AWS ACCESS KEY HERE]',

SECRET: '[AWS SECRET KEY HERE]',

REGION: '[YOUR AWS REGION]',

SQS_QUEUE_URL: '[THE URL OF YOUR SQS QUEUE]',

LAMBDA_FUNCTION: '[THE NAME OF YOUR LAMBDA FUNCTION]'

});

var lib = gistLibrary.load({

"add": "4c7161844cb5280b99c7",

"fib": "9213e3afa774b436edbf"

});

lib.add({

a: 5,

b: 3

}, function(res) {

console.log(res);

});

lib.fib({

n: 10

}, function(res) {

console.log("nth Fibonacci: " + res);

});

If you save this in a file called example.js, you can then do the following:

$ node example.js

Calling Gist with ID: 4c7161844cb5280b99c7

Calling Gist with ID: 9213e3afa774b436edbf

8

nth Fibonacci: 55

Recap

We’ve done quite a bit, so since you’ve come this far let’s recap! Hopefully this post has shown you not only the basic AWS Lambda workflows, but some of the iterative processes involved in sculpting a Lambda function. Our product is by no means production-ready or complete, but with comparatively little code we have created a powerful system for executing Gists in the cloud that is immediately scalable and fault-tolerant. Future iterations could improve upon error handling and leverage promises instead of all our lazy callback hacks.

However, we’ve just scratched the surface of what Lambda can do! In a future Lambda post I’ll be taking this idea one step further by seeing if I can create a Lambda function hosting system using Lambda (so meta, amirite?).

If you have any other ideas for cool applications, I’d love to hear them!

Comments

comments powered by Disqus