Breaking the Chain

Saturday, November 29 2014

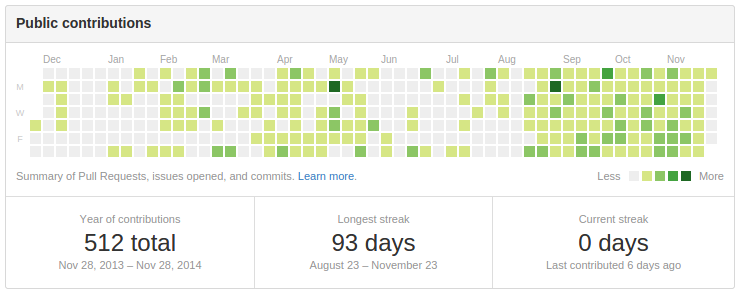

A little under a week ago, I broke the chain.

By “chain” I mean a streak of GitHub commits that went uninterrupted for over three months until, disastrously, unforeseeable events forced me to miss a day. Don’t cry, it’s not the end of the world, a well-meaning mother might say at this point — and indeed there are far worse things in life. But why, then, does it still feel so wrong?

First, a little context. The GitHub commit challenge is nothing new; I first learned of it from this blog post and subsequently stumbled across a guy with an enviably long commit streak. Later I would learn that he wasn’t alone (scroll down to the “other metrics” section). It seemed that all users with such streaks were either at the helm of a massive personal project or spent their days obsessively tweaking their dotfiles. They were also all getting things done.

I’ve never had a problem getting things done. In school I routinely finished assignments days or even weeks in advance, giving myself some much-needed down time in the nights leading up to due dates rather than whiling away in procrastination. But this get-things-done attitude didn’t translate well to projects without due dates…say, my personal GitHub repos. With no rush and no pressure, I simply didn’t feel the need to contribute.

So I decided to try the challenge myself, with the following rather uninspired rules:

- At least 1 commit each day for 100 consecutive days

- No scripting, fudging, or cheating of commit timestamps

- Commits must be significant in nature (e.g. no “removing whitespace”)

93 days. 93 gosh-durn days. So close.

This trick works so well not only because Jerry Seinfeld says it will, but because something about chains seems welded into our very nature. This is why bad habits are notoriously difficult to break, and why breaking them requires a constant, concerted effort. If you’re trying to quit smoking you need to skip the light every single day — even one slip and you’re back where you started. If you’re trying to listen to your dentist and floss regularly, you have to do it every day until it becomes second-nature.

There’s also a thing called the Gambler’s fallacy, in which we tend to perceive completely independent events like coin tosses as being related. If you’ve just tossed a head, how confident are you that you’ll be able to toss another one? How about if you’ve just tossed 10 heads in a row? 100? If you’re playing a fighting game and happen to land a streak of hits, do you feel more or less confident about your ability to win the match? If you’ve won the last five matches, surely you must be able to win this one, right?

It may be that humans like to recognize patterns: a jumble of unevenly-colored commit squares isn’t pretty, an even line of them is. Or maybe it’s because we understand the growing improbability of any ordered sequence of events: tossing 12 heads in a row might happen only once in a lifetime, and is a moment to be remembered. Whatever the reason, continuing a chain seems like the only “right” thing to do. And breaking the chain seems blasphemous.

It’s a powerful motivational tool. Perhaps the most powerful of all. And while it has some shortcomings (such as assuming that humans are perfect machines that never need vacations), in the long run it does exactly what it’s meant to do: get things done.

As for me, I’ve had my vacation. I’m jumping right back on the horse because 93 is proof that I can make it to 100. And I will.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus