Four Things Computer Science Should Teach

Thursday, November 6 2014

I can’t speak for every college in the world when I say that a computer science curriculum, and by extension academia in general, leaves one sorely unprepared for the workplace.

Okay, maybe that was a bit unfair. But having been a computer science major for the past three years — one semester of which was spent as a teaching assistant for intro-level students — I was, shall we say, taken aback when I interned at a large tech company recently. This is what they expect? I learned none of this in school!

Like I said, I can’t speak for everyone; maybe if by some odd twist of fate I had gotten accepted to a prestigious tech school instead, I would have been bestowed with everything I needed to retire from my successful startup at age 25. Still, the hallowed halls of education are a far cry from the industry no matter where you go, and if we are to make the brave transition we’re going to need a whole lot more help.

If I could jump back in time to freshman year, here are the four things I would have wanted to learn most.

Version Control Systems

I am for obvious reasons biased towards git, but whatever the VCS, a graduate should know how to manage their code not only alone but as part of a team. This concept should be introduced fairly early, maybe even in the second semester.

At that point a student is probably still learning their first language: having covered Java’s syntax and basic control structures in the first semester, for example, they would move on to data structures and common algorithms (sorting, etc.). This is by no means a good time to drop the “complexity” of a VCS on anyone, which is why at first it might be a good idea to simply introduce it as a new way to turn in assignments.

Imagine the following scenario: your teacher shows your a “website” (GitHub repo in disguise) where you are to turn in all assignments — naturally the students have already been added as contributors. On the first day of class you were given a step-by-step walkthrough of how to install git. Then your teacher shows you how to git commit and git push. “Remember those two,” you are told again and again. And you do, because how hard is it really to remember two words? So for an entire semester that’s how you turn things in. You finish your assignment, you open up that little window called a “terminal” to type two commands, and it automagically appears on the teacher’s website.

By the time higher-level courses roll around…surprise! You were using this thing called a “version control system” all along. Oh, and look at all the other cool stuff it can do! At that point, students should participate in a group project where committing is part of the grade. When they mess up and cause all sorts of hilarious merge conflicts — and they will — resolving them becomes part of the learning process.

NOTE: Yes, I realize a single repo for all students is just asking for plagiarism to occur; some savvy student could

git pullat the last moment and have the keys to the kingdom. Surely there’s a better way, but for now we’ll assume everyone is an angel.

Right now my university regards VCS as something students should learn on their own. Here’s why that needs to change:

- [Insert some number really close to 100% here] of tech companies use some form of VCS internally, and they’re not going to bother teaching new employees how to use it

- Most students are notoriously good at avoiding extra work

- Students not only need to learn, but learn well

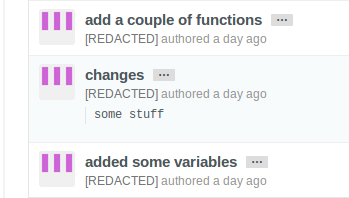

As an illustration of that last point, consider these commits:

These were made by a teammate of mine on a course project I’m currently working on. Anyone with any experience using git is probably trying to claw their eyes out right now, and for good reason. But how is my teammate supposed to know that such a thing as “commit etiquette” exists?

That’s right. By being taught.

Testing

I remember writing JUnit tests for a college project. It was in my junior year, the sixth semester no less, and we weren’t even taught how to use JUnit. It was another one of those “learn it on your own” deals.

That’s cool. I have no problem learning how to use a testing framework on my own, and in fact teaching yourself things is an incredibly valuable skill (more on that later). But in that case why go to school at all? We pay for a college education not to screw around for 1500 days of our lives, but to learn the important stuff.

Testing is important.

The problem is that school assignments are not well-suited for testing. Consider the archetypical example: writing a program to calculate the nth Fibonacci number. It’s a great assignment to throw at students learning a new language because it’s so simple, meaning students can focus on adapting the algorithm to an unfamiliar syntax; I’ve done it in at least 3 different classes already. Here’s a Python version courtesy of Rosetta Code:

def fib(n):

if n < 2:

return n

else:

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2)

You could write a test suite that makes sure this works for fib(0) and fib(1) and assorted other values like fib(15). In fact, this would be a great way to make sure you get an A, since if your program passes all your tests then of course it’s correct, right? (If you answer yes, I pity you.) Arguably, however, it would also be a stupid test.

The other typical example is the assignment on writing getters and setters for properly encapsulated Java classes. Ooh look, I set x to 19 and when I called getX() it returned 19! Success!

In practice tests are never that simple. There are all sorts of considerations like mocking objects, functions, and return calls, finding edge cases, linting, etc. This requires a project complex enough to warrant these testing concepts, and I wouldn’t expect to see such a project in most of my classes. One plausible solution is to give students a fairly large completed project that has errors riddled throughout, and task them with writing tests to uncover and subsequently fix the errors.

How to Google

Let’s try a little experiment, shall we? When I say go, you try answering the question below as quickly as you can with working, compilable code. Ready? Go:

In Java, how do you read a file line by line and print out every other line?

If you instantly knew how to structure the code to read in a file, kudos to you, here’s a cookie. Although I’ve probably written the same code at least ten times, I can’t for the life of me remember it. So you know what I do? That’s right, I Google it.

Let’s repeat that nice and slow. If you don’t know the answer to a programming problem… You. Google. It.

Right after writing that question I decided to test myself, and I was able to find a reasonable solution in about 5 seconds. However, I don’t depend on an IDE for autocomplete (Sublime Text for the win), so writing the correct import statements was the work of a 3-second Google and ample Ctrl+F-ing. Here’s my final solution after about a minute:

import java.io.BufferedReader;

import java.io.FileInputStream;

import java.io.InputStreamReader;

import java.io.IOException;

public class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

FileInputStream fstream = new FileInputStream(args[0]);

BufferedReader br = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(fstream));

String line;

int i = 0;

while((line = br.readLine()) != null) {

if ((i % 2) == 0) {

System.out.println(line);

}

++i;

}

br.close();

}

}

This breaks a few Java best practices, and also I’m rusty. So sue me.

The point is, knowing how to Google is important. I’m constantly amazed by the disparity in Googling skill that I’ve seen between “good” programmers during my internship (and let me tell you, some of these guys were wizards) and intro-level computer science students while I was a TA.

In lab one day, a hapless student popped a question much like the one above. I didn’t know the answer either (what, you expect me to tattoo BufferedReader onto the back of my hand?) so I told him to Google it. Then I watched. And I was mortified. It was a wonder the student managed to find anything, and eventually I had to help him along. “Read a file Java,” I said. Four words. And what do you know, the first hit was a winner.

In another part of the world, I watched expert Googling on a daily basis. Unless you’re one of the venerable greybeards of a large tech company (and they are unfortunately an endangered species), you spend your working hours in a near-constant state of searching: trying to hunt the root cause of a bug here, learning a new framework there. Over the summer this Firefox plugin became my best friend. I chewed through Stack Overflow and system documentation for breakfast, lunch, and occasionally dinner.

From these experiences, I’ve come to believe wholeheartedly that there’s a strong relationship between being a good “searcher” and being a good programmer. I also believe that both can be taught.

How to Think

This might be a bit harder to teach, but it’s perhaps the most important of all.

In many ways, progressing through a computer science curriculum is like doing the 100 meter hurdles. You start off running, and then you come to a hurdle, and you either jump over it or trip and fall and have to make an appointment to see your advisor. Then you repeat until you reach the finish line and get a piece of paper that companies value for no good reason.

In other words, the whole experience is very canned. You learn how to write a for-loop, and then you apply your newfound knowledge, and then you move on to the while-loop. Maybe you learn about databases and then do an assignment or two setting up a database of animals and drawing entity-relationship diagrams. Maybe you take an AI class and read a paper about the Turing Test and watch a few boring videos on genetic algorithms, then try to answer ten homework questions before Friday. Knowledge, knowledge, knowledge, but the application is all on training wheels.

Fun fact: in a real job, your manager isn’t going to ask you ten questions or give you sample code. You’re going to be given an abstract problem and unrealistic expectations, and then set free on your rickety bike with no training wheels. Good luck.

This past semester, I’ve noticed that I do remarkably little thinking in college. Sure, there’s thinking involved in trudging through assignments and digesting textbook material, but it’s not the active creative kind I’ve learned to associate with the workplace. I’ve also noticed the same trend in other students, and if the only programming they do is for school, then they are disastrously unprepared for applying their knowledge after college ends. Or, as this amazing article about learning math says:

“Teachers can inadvertently set their students up for failure as those students blunder in illusions of competence.”

But, how to teach someone to think? Here I don’t mean thinking so much as I mean applying programming concepts to real-world problems, which does indeed require a level of creative thought several orders of magnitude above anything you see in school. Is this something that can even be taught?

A colleague of mine now working towards his PhD is pondering the very same questions. He believes, as the article about math above does, that what’s missing is a fundamental understanding of programming concepts at the very beginning. We finish canned assignments and get passing grades and so are led to believe we “understand” programming, but when we see something novel we are unable to apply what we’ve learned, most likely because we don’t have enough practice. It’s a 10,000 hour sort of thing.

Which brings me to…

The Secret Ingredient

Okay, so if you become a programming virtuoso through years of grueling practice, are you willing to invest all that time and effort? Most freshmen probably wouldn’t. I myself chose computer science because I wanted to learn how to make video games, and was very nonplussed by discrete math in my first semester. The thought of rote programming would turn me off very quickly, but our goal is to make computer science more inviting to the masses.

So here’s what I tell people when they ask me how to become a better programmer (for some odd and undeserved reason I’ve been getting that question a lot recently): think of something you really want to make, and make it.

This is the secret ingredient. A DIY project outside of school or work, on your own free time.

The first trick to this exercise is to disregard everything you think you know or don’t know. Set unrealistic goals. Make the next Facebook. The first hurdle you’ll have to overcome is turning this lofty dream into something tangible. What language will you use? Will you need a database? What will your product look like? What colors will it be in? Decisions, decisions. All requiring a measure of knowledge and creative thought to answer.

Chances are you won’t know what you need to know right away. Maybe you’ve never set up a web server before (if your project happens to require one), so you’re going to need to learn how. That’s right…Google to the rescue.

Learning something as “out there” as setting up your own web server when you have absolutely no web experience has the advantage of honing one of life’s great skills: autodidacticism (no, I didn’t know that word off the top of my head, Google to the rescue again). Some of us are gifted with the amazing ability to be self-taught, but for others it’s like being thrown into the lion’s cage with a juicy steak on the first day of the new zoo job. However, like anything else, it’s a skill that can be improved over time. Yes, you might get mauled the first few times. But soon you’ll be slinging steaks with the best of them.

Whatever your project, I would only hope that you use a VCS to manage it and write ample tests. Just a suggestion.

As you can see, working on a DIY project can make up for any shortcomings of being a computer science major and then some. But there’s one more benefit: it keeps you interested. Tired of writing the Fibonacci sequence? Can’t think of why you’d want to know how to print out every other line of a text file? Having second thoughts about programming as a career? Make a website. Or a sweet app. Or a game to amaze your friends.

Do what you’ve always wanted to do. You’ll be surprised how much you learn, not only about programming, but about yourself.

Honorable Mentions

A few others I just couldn’t pass up, but which are decidedly less important:

- Interview questions

- How to build your portfolio and tech/online presence

- Agile development and sprints

Comments

comments powered by Disqus